Sometimes it seems that even the most mundane of occurrences are just the tiniest tip of something global in nature. Take for example something I noticed during a visit to a local teriyaki restaurant on Friday. There was a sign at the counter stating that for the time being the usual free hot sauce—meaning this stuff...

...would not be supplied because of a "shortage" of chili peppers. Personally, I have a “sweet tooth,” and not into anything too “hot” or “spicy,” but apparently some people are. According to a recent story in The Guardian,

Sriracha lovers everywhere are feeling the not so pleasant sting of the beloved hot sauce shortage, now in its second year. Drought in Mexico has resulted in a scarcity of chili peppers – in particular, red jalapeños, the raw material of sriracha – leading Huy Fong Foods, the California-based maker of the iconic condiment, to scale back production.

“It is a challenging crop to grow,” said Stephanie Walker, a plant scientist at the New Mexico State University, who serves on the advisory board of the Chile Pepper Institute. “Jalapeños are really labor intensive, requiring people to de-stem them by hand before they go for processing.”

The current drought in northern Mexico has been on-going for two years, and most of the reservoirs in Mexico are near empty, which of course affects lives and livelihoods. And it isn’t just in Mexico, of course. The World Meteorological Organization a few days ago tells of the “vicious cycle” of “climate change” in Latin America and the Caribbean that is “spiraling out of control”:

Extreme weather and climate shocks are becoming more acute in Latin America and the Caribbean, as the long-term warming trend and sea level rise accelerate…Temperatures over the past 30 years have warmed an average 0.2° Celsius per decade – the highest rate on record…Thus, for instance, prolonged drought led to a drop in hydroelectricity production in large parts of South America, prompting an upsurge in demand for fossil fuels in a region with major untapped potential for renewable energy.

Extreme heat combined with dry soils to fuel periods of record wildfires at the height of summer 2022, leading carbon dioxide emissions to spike to the highest levels in 20 years and thereby locking in even higher temperatures. Glacier melt has worsened, threatening ecosystems and future water security for millions of people. There was a near total loss of snowpack in summer 2022 in the central Andean glaciers, with dirty and dark glaciers absorbing more solar radiation which in turn accelerated the melt.

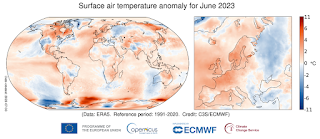

This map from the WMO shows how surface sea temperatures in June are well over the "norm" this year (partly exacerbated by the "El Nino" affect) compared to the "average" of the past 30 years, although not affecting the U.S. as much as other parts of the world:

This map shows that while “only” about half the U.S. is experiencing above normal temperatures, all of Mexico and Central America, Canada, Africa and Western Europe is experiencing such:

But who cares about what’s happening over there, it’s not our “problem,” right? Well, that’s what Republicans of this sort…

…wish the population to be fooled by. Waterworld or Interstellar is for our “future," and we can't "change" that, so just let it "flow." Fool people into thinking that “paradise” awaits all “true believers,” most of whom deserve to rot in Hell for what they are doing to this planet "God" created for them.

We are told that northern Mexico is partly dependent on rapidly depleting Colorado River water for irrigation. But wait: doesn’t nearly all of that river flow through the U.S.? The National Audubon Society tells in a report last month that decreasing flows are having a devastating effect on bird habitat, but it doesn’t forget people:

Climate change is upending status quo management in the Colorado River Basin faster than state and federal managers anticipated. Warming temperatures are drying the landscape, the river’s flows have declined 20% from the 20th century mean, and reservoirs have dropped precipitously to the point that threatens the water supply for 40 million people. Stabilizing the basin’s water supply system is important to avoid water supply crises that make it difficult for elected leaders to prioritize environmental considerations. But that cannot be the limit of federal effort if we want a future with thriving communities and wildlife.

Last April, ABC News reported that “The Colorado River is now considered the more endangered river in the world by conservation nonprofit American Rivers,” and its use has been “over-allocated” despite its record-setting depletion. This isn’t just something happening “other there,” anymore, but something that affects the entire economy and food supply:

The river system supports $1.4 trillion of the annual U.S. economy and 16 million jobs in California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming-- equivalent to about 1/12 of the total U.S. domestic product, economists at the University of Arizona found in 2015. More than 90% of the country's winter leafy greens and much of its vegetables are grown in the Arizona’s Yuma Valley—the state that would experience the most drastic water cuts under current regulations.

Lake Mead, which is fed by the river, was considered simply too “big to fail" until this year, when it was put on the endangered “watch” list:

Lake Mead was producing 25% less hydroelectricity as its elevation reached a record low at 1,067 feet in December 2021. The reservoir was dangerously close to hitting dead pool status, when water levels are too low to flow downstream to generate power, last June as surface elevation measured in at just 1,043 feet.

Here in the state of Washington, four of the six months of the “wet” season were not only below normal, but far below normal for precipitation. Climate in Western Washington is problematic in its unpredictability; last year we saw much higher than normal precipitation through June, but then saw drought conditions for four months, well into October when we were still seeing 80+ degree days.

This year, the “wet” season, although being well

below normal both in temperatures and precipitation, saw no

sustained “dry” spells, just a little bit here and a little bit there, so it was easy to be "fooled" that there really wasn't a "problem." We are

currently into a “dry” spell after a close to “normal” June, and if it continues like last year it could be an even worse wildfire season.

But California, which has had seven-year drought spells, has been experiencing a series of “atmospheric rivers” that have been “pummeling” the state for six months. Yet there is a question if this is either an anomaly or the new “normal." According to ABC News:

In the future, the trend will be for greater, longer, more protracted droughts interrupted occasionally, by periods of plentiful rainfall, scientists say. This year will be an "important case study" on how much of the water that was lost in the past five years from the largest reservoirs can be recovered, (Zach) Zobel said. "If things can't recover in the good years, then the situation is still not looking good for the future," Zobel said. Climate scientists don't expect many "average" years of precipitation anymore, Zobel said. Instead, what will likely happen is either all of the precipitation will come at once, or none at all -- what is referred to the "boom or bust precipitation pattern," he said."

Meanwhile, the supposed “saviors” are the huge underground aquifers like the Ogallala and newly discovered Fenner aquifer, of which a major battle is occurring concerning whether it should be used now as a replacement for lost water, or “saved” for a “rainy day.” The problem with the 700-mile long Fenner aquifer—called “fossil water” since it was created pre-human habitation and has no natural method of replenishment today—is that it is being used by a private company with no regulation on its use. The Atlantic points out that “Once we use it, it’s never coming back. And unless the aquifer is actively refilled, its depletion could have serious consequences for ecosystems above ground.”

The company that is being allowed to drill wells into the aquifer, Cadiz, Inc, which currently is using wells for irrigation, is planning on digging more wells and building pipelines to Southern California for profit. The Atlantic points out that this should be seen as a short-term, short-sighted solution to water supply issues by unethical operators, and “that water management in the age of climate change requires not just new pipes, but also new paradigms."

Although “The Fenner aquifer should be seen as ‘an emergency supply,’ according to the University of New Mexico anthropologist David Groenfeldt, who says ‘How can we possibly justify using it now?,” others simply say “why not?” That is an easy thing to say, with water shortages, wildfires and lawns that need to be watered; but the next question is when the underground aquifers—which much of the country relies on for its water supply—simply run out because there is no restrictions on their use, and unlike surface water will never come back during a human timeline, then what? Will we need a massive new effort to desalinate sea water, and how expensive will that be? Or will we need to take climate change and greenhouse gases seriously?

Or will we just sit back and wait for “paradise” to take us while future generations live in a kind of “Hell” we created for them?

No comments:

Post a Comment